Issue 378

A notebook about how we work, and learn, and love and live.

“You get further in life by avoiding repeated stupidity than you do by striving for maximum intelligence.” — Charlie Munger

This week Debbie and I spent a few days on the beach with an old friend. I read books and magazine articles instead of my screens. We visited the Quaker gravesite of the very first Anthony to come to America (Susan B. and I descend directly from him). We ate fresh seafood on an outdoor deck overlooking a harbor. We told stories, we shared vulnerabilities. Doing ‘nothing’ is so rewarding. I highly recommend it.

Happy Friday.

Personal Development

Forcing ourselves to do things doesn’t work.

Speaking of doing nothing, in a couple of weeks Guardian writer Oliver Burkeman’s new book, one that recommends setting aside efficiency ‘solutions’ in favor of finding joy in the ‘finitude of human life’, will be released.

“The average human lifespan is absurdly, insultingly brief. Assuming you live to be eighty, you have just over four thousand weeks.

“Nobody needs telling there isn’t enough time. We’re obsessed with our lengthening to-do lists, our overfilled inboxes, work-life balance, and the ceaseless battle against distraction; and we’re deluged with advice on becoming more productive and efficient, and ‘life hacks’ to optimize our days. But such techniques often end up making things worse. The sense of anxious hurry grows more intense, and still the most meaningful parts of life seem to lie just beyond the horizon. Still, we rarely make the connection between our daily struggles with time and the ultimate time management problem: the challenge of how best to use our four thousand weeks.”

This week in his own newsletter, The Imperfectionist, Burkeman pointed to a 2010 blog post that inspires him, by mediation teacher and writer Susan Piver, called Getting Stuff Done by Not Being Mean to Yourself. Push less. Enjoy more. Get more living done.

Book Review: Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals

Systems Thinking

One way to begin understanding complex systems is by describing them in detail.

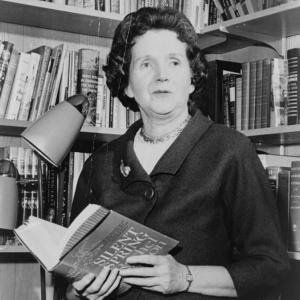

Rachel Carson chronicled events in the oceans, from the cycles of plankton growth to the movement of waves, in accessible, evocative descriptions. (Image via National Women’s History Museum.)

“One way to begin understanding complex systems is by describing them in detail: mapping out their parts, their multiple interactions, and how they change through time. Complex systems are often complicated—that is, they have many moving parts that can be hard to identify and define. But the overriding feature of complex systems is that they cannot be managed from the top down. Complex systems display emergent properties and unpredictable adaptations that we cannot identify in advance. But far from being inaccessible, we can learn a lot about such systems by describing what we observe.”

Futures Thinking

How to build hope for a collective vision of the future.

New York World’s Fair — Unisphere & Flag Display

“While most have heard of the World’s Fairs, few know how important they were in shaping our culture. Drawing more than 60 million guests in the 1960s alone, these 6-month long mega-events gave us a place to celebrate our achievements and experience the future up close and in person. They promoted a collective vision for a better world — reminding us how connected we were and how far we could go if only we went together.

“The Fair’s concept was invented by Great Britain in 1851, when “The Great Exhibition” of London unified Britons around the idea that technology was the key to unlocking a better future for their country. In 1889, Paris hosted the Fair, building the Eiffel Tower and showing 32 million guests the latest wonders of science and technology. Intent on one-upping Paris, Chicago hosted the Fair in 1893, drawing 27.5 million guests — nearly 40% of the U.S. population before there were cars, planes, or highways. Guests saw a city illuminated by electricity for the first time, marveled at the architecture that would inspire the City Beautiful movement, and rode the world’s first Ferris Wheel.

“In the decades that followed, World’s Fairs continued to amaze guests from around the world. They debuted the steam engine, the telephone, the Model T and its assembly line, broadcast television, and touchscreens. They are responsible for symbols of progress that stand to this day, like the Eiffel Tower, San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts, and Seattle’s Space Needle. They spread the ideas of some of history’s most influential people like Walt Disney, Amelia Earhart, Booker T. Washington, and Albert Einstein. They inspired millions of children, including Carl Sagan and Neil DeGrasse Tyson, to marvel at our universe and the cosmos.

“Unfortunately, this all started to change after the U.S. put a man on the moon. While this was certainly a “giant leap for mankind,” we lacked an understanding of what our next step would be. Without a new North Star to guide us, we stopped moving forward and our vision for the future began to fade. This all came to a head when the U.S. hosted its last Fair in 1984. Tired and dated, it ended in bankruptcy — symbolically extinguishing our hope for a collective vision of the future.”

Transformational Economy

Many worthy efforts to invent a new kind of economy are falling short of their transformational potential.

Photo by Carlos “Grury” Santos on Unsplash

“For too long, economic theories and practices have contributed to a range of destructive outcomes, such as extreme wealth inequality, conflicts over resources, and degradation of the world’s ecosystems. A plethora of experiments and new theories have attempted to address these issues, loosely held within the rubric of the next economy… However, many worthy efforts to invent a new kind of economy are falling short of their transformational potential.”

Article Series: Whole Systems Economic Development: A Regenerative Approach

Learning

Countering violent extremism.

I think you want to know about Harper Reed. Amongst other things (a whole lot of them) he curates a Twitter feed of journalists and researchers talking about countering violent extremism.

Twitter feed: Countering Extremism

Visual Identity

The real Olympic blood sport? Debating the official logos.

Social Messaging, Advertising

“This isn’t a solo performance.”

“Some people can’t get a vaccine. So it’s an ensemble effort, to make sure that they’re protected, too.”

“Two new spots have landed overnight that many are suggesting are the right way to get a needle into Australians’ arms and, even more interestingly, both were created in-house by people who’d never made ads before.”

Playlist

Watch this. I guarantee that it will make you smile. I guarantee that it will make you believe in humanity.

Video: Stand Here for Dance Party

Image of the Week

The image of the week was shot by photographer, Cade Martin, for the March of Dimes. I snagged it from Workbook Winners: Comm Arts 2021 Photo Annual.

What’s Love & Work?

If you’re new to Love & Work, it’s the weekly newsletter by me, Mitch Anthony. I help people use their brand – their purpose, values, and stories – as a pedagogy and toolbox for transformation. Learn more.

If you get value from Love & Work, please pass it on.

Not a subscriber? Sign up here. You can also read Love & Work on the web.